Camp Oliver

The Alabama Fisherman’s and Hunters’ Association’s 100th Year

By Seth Self, Black Warrior Riverkeeper intern through The Curtis and Edith Munson Foundation’s Scholarship at The University of Alabama

Sherman Engler, immediate past president of the Alabama Fisherman’s and Hunters’ Association, boating on the river near Camp Oliver. Photo by Seth Self.

2022 is a year of milestones for water in Alabama. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Clean Water Act, a landmark piece of legislation aimed at protecting America’s waters passed by Congress with bipartisan support, as well as the 20th anniversary of the founding of Black Warrior Riverkeeper, a nonprofit organization dedicated to maintaining the health of the Black Warrior River watershed.

2022 is also a milestone year for another organization; the Alabama Fisherman’s and Hunters’ Association is commemorating its 100th anniversary this year.

As a public relations student currently interning with Black Warrior Riverkeeper through the Curtis and Edith Munson Foundation’s scholarship at The University of Alabama’s College of Communication and Information Sciences, I seek to support the clean water advocacy organization’s mission in all things related to communication. One of the best ways to do this is by telling the stories of those impacted by not only Black Warrior Riverkeeper, but those who live along the river.

One such individual is Sherman Engler, the immediate past president of the Alabama Fisherman’s and Hunters’ Association. I drove up from Tuscaloosa to his home along the Black Warrior to meet with him and interview him about the association and the river.

As I arrive at his home at Camp Oliver, the headquarters of the association, it’s clear from the start the importance of the river. The camp is nestled along a gentle slope toward it, near a wooded area on the border of Jefferson and Walker Counties. He and his wife, Tonie, greet me and welcome me into their home, the river’s beauty visible through the windows of their house that faces its waters.

Camp Oliver, headquarters of the Alabama Fisherman’s and Hunters Association. Photo via Sherman Engler.

We sit at their table, and the interview begins with a question about the Alabama Fisherman’s and Hunters’ Association. What is the pitch, I ask? What does the organization do and how would you explain it to a stranger?

“Our organization was really founded by early sportsmen, who wanted a place to fish and hunt and not have any abuse of the river or waterways,” Engler says. The organization has sought to continue that mission ever since by advocating for waters across Alabama.

Founded in 1922, the group got its start in northern Jefferson County. Engler recounts the story of William Oliver, the namesake of the camp on which he lives and where the organization is headquartered, fishing on Shades Creek. Oliver, a businessman in Birmingham, had discovered that fish in the creek were being killed by dynamite. In response, he petitioned the city of Birmingham and the state of Alabama to respond with laws to stop it. As Engler states, when the response included a directive to Oliver that he must form a political group to advocate for those new laws, the forerunner to the The Alabama Fisherman’s and Hunters’ Association was born. Oliver formed the Jefferson Fishermen and Hunter’s Association, named for a local resident, and began lobbying for new conservation laws that eventually passed.

“There was really no conservation effort, or anything done in terms of keeping the variety of fish and numbers of fish in a consistent manner,” says Engler about this issue. That is why it was such an important deal for Oliver to have successfully lobbied for those bills to pass, as they were the first of their kind for the state.

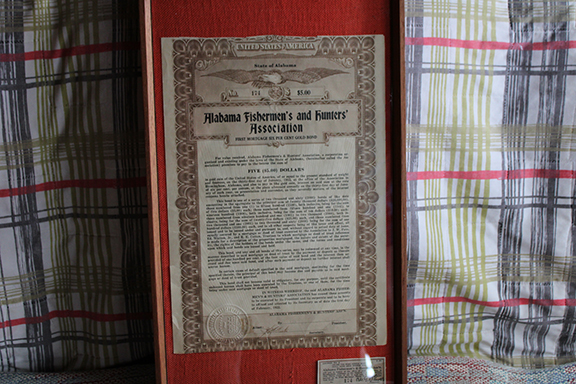

At that point, Engler says, the group became the Alabama Fisherman’s and Hunters’ Association that exists today. The group purchased 90 acres of property (what would become Camp Oliver) along this part of the Black Warrior River, raising money by selling bonds for five dollars. After the purchase, the group built bunkhouses and a kitchen. Dorms from a nearby World War I-era hospital were also moved onto the property, and for two dollars a year, members could come down and fish.

By 1925, there were over 800 members from all walks of life, both rural farmers or city dwellers from Birmingham. Engler says this spot was perfect for the camp, as the location already attracted lots of traffic: the nearby farming communities meant it was already populated, and the ferry that once ran across the river provided transportation. There were also gravel roads that eventually connected to Birmingham.

The Alabama Fisherman’s and Hunters Association purchased 90 acres of property (now Camp Oliver) on Black Warrior River, by selling these bonds for five dollars. Photo by Seth Self.

By the wartime years of the early 1940s, the growth of the organization had slowed due to World War II. It was also during the 1940s that the state of Alabama was exploring building a dam downstream from the camp to raise the river’s water levels, in order to extend the port system further north from Northport. When this was completed in 1947, that goal was met; the port system now ran all the way to Birmingport in Jefferson County.

Additionally, water levels at Camp Oliver rose and claimed over half of the original property. Engler points through his window to the river, and motions to me just how much land was lost. He points to where the original property extended, which is now almost halfway across the river as it flows today.

When the waters rose, Engler says the organization decided to split Camp Oliver into lots for purchase by families who wanted to live in the area year-round. Until that point, with no electricity or water, most families only came to the area for a few weeks at a time. However, with the addition of those technologies in the 1960s and 1970s, many people sought to move here full time.

Engler says it was perfect timing, and many of those families bought the aforementioned lots when the camp was divided into its current form. One such family still has a member who lives at the camp alongside Engler; Bill Hoster, the grandson of Lewis Hoster, Jr., an original member of the association, still resides here.

This is how the camp appears to me as we walk through the property. There are many houses, most of which were built from wood from the area at an old sawmill that used to exist on the camp’s grounds. There is also a park on the property, which Engler says they plan to utilize for 100th anniversary celebrations.

At this point, it has become clear to me how much the property means to Engler. So, I ask him how he got involved in the camp. He and his wife smile before answering.

“Well, I was born into it, so to speak,” he says.

He recounts that his grandfather joined the organization in 1927 and helped support it financially. Eventually, his grandfather became the organization’s president, followed by his father. When Engler and his wife moved back here to Alabama in 1999, many in the group jokingly warned him he might find himself nominated for the position as well.

Those predictions came true, as Engler served as president from 1999 to 2020. It was during his presidency that the organization became connected with Black Warrior Riverkeeper. Engler says when they learned about Black Warrior Riverkeeper, they immediately contacted Charles Scribner, the organization’s executive director, to get connected. Though others now serve in leadership roles, such as Hugh Rushing, the vice president and treasurer, the organization remains involved with the Riverkeeper.

“When there’s ever a Riverkeeper event, down here at the river, we try to support that as much as possible,” Engler says of the association’s relationship with Black Warrior Riverkeeper. The organization held meetings at Camp Oliver for a few years, and has held cleanups here before. Engler has been a member of Black Warrior Riverkeeper’s Advisory Council for many years.

Most of the group’s work takes place strictly here at the river and camp site, Engler says, which is separate from Black Warrior Riverkeeper’s work that takes place all over the river’s 17-county watershed. For example, Engler says the association hosts river clean-ups, and that it has a work boat he can take out on the river for any needs.

Boats at Camp Oliver. Photo by Seth Self.

Engler then offers to take me out on one of the boats he owns, and I gladly accept. This particular boat is a 1937 model once owned by Dr. William Smith, a founding member of the organization. We go for a short ride out on the river, where Engler points out the edges of the camp and the sandbar in the middle of the river that marks where the camp originally extended prior to the water level rise in 1947.

As we return from the ride, I am overwhelmed with the peacefulness of the river and the serenity of the scene; it reminds me of the small river behind my house in Cullman, that eventually feeds into this river itself. It is no small wonder that someone like Engler, or those in his group or in the Riverkeeper organization, have fought so hard to keep this river clean. I begin to think of all those who have enjoyed it before me, and the stories they must have about its waters. Engler offers a story about Leah Marie Rawls Atkins, a history professor who once won a world skiing championship along these shores and the first woman inducted into the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame, as an example of one such person who has long loved this river.

Engler tells me the river was not always this clean, either, and that it has definitely improved over the decades since both the dam’s construction in 1947 and the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972. Numerous species of animals are “flourishing here,” as he says, including otters, the bald eagle and the white pelican.

Many of Black Warrior Riverkeeper’s efforts have helped to make the river cleaner as well, such as the recent addition of Katie Fagan, a full-time staff member dedicated to organizing litter cleanups. Further, Black Warrior Riverkeeper has also helped promote a new tool into those cleaning efforts: Litter Gitters, devices designed by Mobile-based Osprey Initiative that sit atop the water of a river to capture trash. Several of these traps have been installed in or near Birmingham to keep litter from the city from traveling downstream; Engler says he’s noticed a litter reduction around the Valley Creek area of the river near Camp Oliver..

Riverkeeper volunteers from across the watershed, oftentimes students from The University of Alabama, also organize their own clean-ups to help keep the river healthy. Additionally, as stated earlier, this year is the 50th anniversary of the Clean Water Act; that law has also undoubtedly played a role in ensuring the health of rivers such as the Black Warrior in the last few decades.

As the interview winds down and I thank the Englers for having me, I begin to think about all the change that the river has seen. From the dam and water level, to its overall health improving from numerous efforts, many things seem to have changed.

But it seems that the most important things haven’t changed at all. The Alabama Fisherman’s and Hunters’ Association still continue to protect the river. Black Warrior Riverkeeper still patrols and advocates for it. Volunteers and students like me still come to it, to give time and effort to clean it and write about it. People still live on it and love it. And individuals such as Sherman Engler will always devote service to help save it.

Some of the abundant wildlife on the river near Camp Oliver. Photo via Sherman Engler.